On 30 November 2024, we mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Sir Winston Churchill, one of the most recognisable and memorable figures in British history. Churchill gained a reputation for his memorable speeches, even after his time as prime minister came to an end, and he is best known for leading the nation to victory during the Second World War.

However, it was his experiences as a young man in the Queen’s 4th Hussars and working as a war correspondent that shaped his later life. Churchill’s resilience in serving his country ensured that his legacy will be remembered for decades to come. We celebrate the life of Sir Winston Churchill and pay homage to his remarkable legacy with four collector sets that bring together a 2024 UK £2 coin with medals and a number of historic coins.

Early Years

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born on 30 November 1874 at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire. The eldest of two sons, Winston was born into aristocracy, which meant that he was raised by a nanny, Mrs Everest, rather than by his parents, Lord Randolph Churchill and American socialite Jennie Jerome. The young Churchill admired his mother from afar but it was to Mrs Everest that he would confide his worries.

“It was to her I poured out many troubles,

both now and in my schooldays.”

Mrs Everest passed away when Churchill was a young man of 21 years old and he was devastated by her death. He arranged for a headstone to be erected on her grave and continued to pay an annual sum for its upkeep until his death, a practice that has been continued to the present day by the International Churchill Society and the Churchill family.

Education and Sandhurst

“It was at ‘The Little Lodge’ I was first menaced with Education.”

Shortly before he turned eight years old, Churchill was sent to boarding school to further his education. However, he did not enjoy the years that he spent at boarding school. Expected to study traditional subjects such as Greek and Latin, which he struggled with, Churchill often did poorly in examinations and this led his father to think that his son wasn’t academically inclined.

One day, whilst Churchill was playing with toy soldiers in his room, Lord Randolph visited him and asked if he would like to go into the army. He had always been fascinated with military theory and tactics so agreed, and all efforts henceforth became focused on ensuring that Churchill would be able to enter the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst. Although this seemed impossible at first, after Churchill was admitted to a crammer school, he eventually qualified for a cavalry cadetship on his third attempt.

Lord Randolph was unimpressed with this ambition to join a cavalry rank and instead suggested that Churchill would be better suited to join the infantry of the 60th Rifles when he left the military academy. In contrast to his experience in school, Churchill excelled within the military academy, passing out of Sandhurst eighth in a batch comprising 150 men at the end of his tenure.

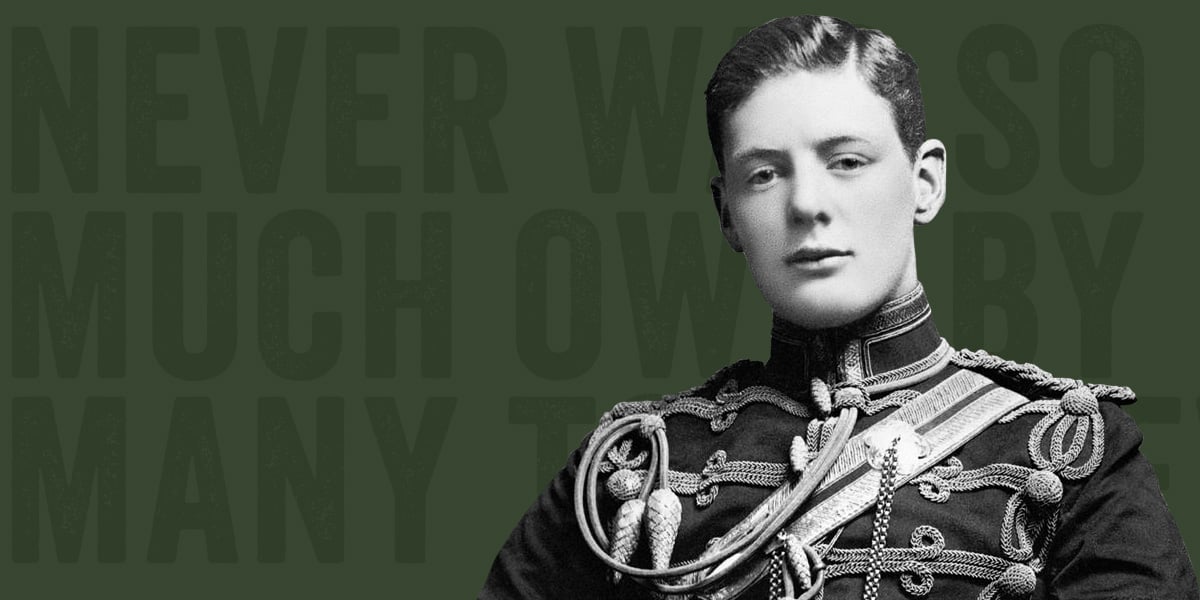

The Queen’s 4th Hussars

Churchill performed well at Sandhurst and caught the eye of Colonel Brabazon of the Queen’s 4th Hussars, a cavalry regiment in the army. The colonel was keen to acquire Churchill for his regiment and approached the young man with an offer to join him. However, Lord Randolph was unhappy with this change of plan. Churchill’s father still wanted his son to join the infantry regiment of the 60th Rifles and had already asked the Duke of Connaught if he could join the regiment before his son had completed his education at Sandhurst.

Churchill was determined to join the 4th Hussars after having his head turned by Colonel Brabazon. He implored his mother to talk to his father to persuade him to let him join this cavalry regiment instead of the infantry regiment that had already been planned for him. At this time, Lord Randolph was suffering with ill health and eventually relented.

‘My mother explained to him how matters had arranged themselves, and he seemed quite willing, and even pleased, that I should become a Cavalry Officer.’

In 1895, Churchill joined the 4th Hussars and the following year, he travelled to India with the regiment, taking part in several polo tournaments between regiments.

‘… the 4th Hussars exceeded in severity anything I had previously experienced in military equitation.’

Working as a War Correspondent

‘The military year was divided into seven months’ summer season of training and five months’ winter season of leave, and each officer received a solid block of two and a half months’ uninterrupted repose. All my money had been spent on polo ponies, and as I could not afford to hunt, I searched the world for some scene of adventure or excitement.’

Although Churchill had joined the Queen’s 4th Hussars, he hadn’t experienced much conflict before his 21st birthday. He had a romantic view of battles and was eager to experience this first-hand, so asked if he could be sent to Cuba during leave from his regiment to see the combat between the Spanish and the Cuban rebels.

‘The 30th November was my 21st birthday, and on that day for the first time I heard shots fired in anger, and heard bullets strike flesh or whistle through the air.’

During this time, Churchill decided that he could make additional money to his army wages by working as a war correspondent and sent anonymous letters to the newspapers back home. This marked the start of his work as a war correspondent and he would go on to write letters about other conflicts that he also witnessed first-hand.

This pursual of additional work alongside his military duties became a point of conflict for General Kitchener, who disliked a young officer criticising his superiors in print. Compounded with the fact he earned more money writing, Churchill decided to leave the army and instead focus on a career as a writer.

‘… I felt a new way of making a living and of asserting myself, opening splendidly before me. I saw that even this little book had earned me in a few months two years’ pay as a subaltern.’

During the Second Boer War in 1899, Churchill secured a position as a war correspondent for the Morning Post and travelled to South Africa to write about what he encountered there. Whilst he was on his way through what was formerly known as the Natal province, the armoured train he was on became derailed in an attack by the Boers. Churchill sprang into action to ensure the wounded escaped but on returning to the scene, he was captured by the Boers as a prisoner of war.

‘Yet this misfortune, could I have foreseen the future, was to lay the foundations of my later life.’

Escape from a Boer Prisoner-of-War Camp

Churchill was escorted to a prisoner-of-war camp in Pretoria where he planned an escape with his fellow officers who had also been captured. His opportunity for escape presented itself after three weeks of captivity, when Churchill was able to climb over a wall when two sentries had their backs turned. He strolled out into the wilderness where he took refuge before sneaking onto a train that carried him to a mining community.

When he arrived at this community under cover of darkness, Churchill was able to find British citizens who helped him hide inside one of the mines until patrolling Boers had left the area. They further helped him to flee the country by stowing him away on another train carriage and he eventually made his way to the safety of Portugal.

Here, Churchill read newspapers that declared massive defeats for the British army across South Africa since his capture and subsequent escape, which inspired him to return to the army before he turned to a dream he had harboured since boyhood – entering Parliament.

Entrance into Parliament

As a young boy, Churchill had witnessed his father debating in Parliament on several occasions. He had also witnessed other young men who had been voted into Parliament being welcomed into the House of Commons by their fathers, who were also MPs, but this was sadly not the case for Churchill as his father Lord Randolph passed away shortly before he had joined the 4th Hussars.

‘All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support, were ended.’

Nevertheless, Churchill never lost his dream of entering Parliament, and the notoriety that he gained as an escaped prisoner of war led to his election in the constituency of Oldham in England.

Originally a Conservative politician, Churchill dramatically crossed the floor to the opposition at the start of his political career to join the Liberals, before switching back again before the Second World War. He also held several roles throughout his time in office as a politician.

Clementine Hozier

In 1908, Churchill was invited to a dinner party that he was reluctant to attend. Running late, he found himself placed in the only seat available, which was next to his future wife Clementine Hozier. The two became engrossed in conversation for the rest of the evening and their wedding took place just six months later.

Throughout their marriage, Clementine became a sounding board for Churchill’s political ideas. When they were apart, the couple would often write letters to one another, even communicating strong feelings with one another in this way when they were in the same house.

First Lord of the Admiralty

In 1911, Churchill was appointed as the First Lord of the Admiralty, a coveted position that saw him become the civilian head of the Royal Navy. After taking up the post, he spent the first eight months of his 12-month post in office aboard the Admiralty yacht Enchantress, visiting every capital ship and Royal Naval base in the British Isles.

Churchill became instrumental in reshaping the Royal Navy, introducing larger, more powerful ships and converting these from coal to oil. The changes he implemented during his time in office would be crucial for preparing the Royal Navy for the First World War.

However, his time as the First Lord of the Admiralty ended after the disastrous Dardanelles campaign and the Gallipoli landings. Churchill eventually resigned from government and went to serve on the Western Front until early 1916.

Painting as a Pastime

After the disastrous Dardanelles campaign of 1915, Churchill was removed as First Lord of the Admiralty and feared that this was the end of his political career. He was left with ‘long hours of utterly unwonted leisure in which to contemplate the frightful unfolding of the War … And then it was that the Muse of Painting came to’ his rescue.

In times of stress, Churchill became reliant on painting as a distraction and to help him unwind, finding the hobby therapeutic. His preferred medium was oil paints as he felt they were superior to watercolours. He continued to paint for the rest of his life, producing more than 550 paintings during his lifetime.

‘Painting is a companion with whom one may hope to walk a great part of life’s journey.’

Bringing Back the Gold Standard

In 1924, Churchill was elected in the constituency of Epping and was subsequently offered the role of Chancellor of the Exchequer in Stanley Baldwin’s government, the highest ministerial post that was once held by Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, this also made Winston Churchill the Master of the Mint.

The Bank of England had advocated for a return to the gold standard and, although initially reluctant, Churchill announced its return in the April 1925 budget statement. This decision led to restrikes of The Sovereign taking place for a short period that were then sent to the Bank of England’s vaults.

However, the return of the gold standard didn’t stabilise the economy as intended and instead caused economic instability that led to the Great Strike of 1926. The Great Depression of 1929 sent the global economy spiralling, and Britain eventually abandoned the gold standard in 1931.

Winston is Back

When Adolf Hitler was elected as German Chancellor in the years preceding the Second World War, Churchill was vocal in his warnings against the rearmament of Germany. He spoke about this topic in the House of Commons and wrote articles in the press but was dismissed as a warmonger.

However, after the Munich Crisis and the occupation of Czechoslovakia, the tide of public opinion began to turn in Churchill’s favour. Following the invasion of Poland, he was invited back into government as the First Lord of the Admiralty for a second time. A signal went out across the British fleet declaring ‘Winston is back’, whilst Churchill received a message of congratulations from US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Second World War Leader

When war with Germany became certain, Churchill was elected as the prime minister of Britain’s coalition government and the years that followed went on to become some of the most memorable of his tenure in Parliament.

‘I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat’.

Churchill orchestrated the rescue at Dunkirk in 1940, which saw nearly 350,000 British and Allied troops rescued to British soil. Although things appeared hopeless, Churchill was determined to boost morale across Britain and delivered some of his most memorable speeches during this time. Throughout the Second World War, he remained a vocal adversary to Hitler and worked with the Allied leaders to ensure victory across Europe.

Despite his success during the Second World War, the Conservative government led by Churchill lost the 1945 election and he resigned as prime minister.

Although Churchill is more famous for his first stint as prime minister, he returned to the role for a second time in 1951. However, this proved to be short-lived, as periods of ill health eventually led Churchill to reluctantly resign from the role in 1955 at the age of 80.

Knighthood and Nobel Prize for Literature

In 1945, Churchill was first offered a knighthood by George VI but refused the honour, telling the king, ‘How can I accept the Order of the Garter, when the people of England have just given me the Order of the Boot?’ However, in 1953 he later accepted the offer from Elizabeth II, George VI’s daughter.

That same year Churchill was given the Nobel Prize in Literature ‘for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values’. During his life, Churchill wrote 43 books that included recounts of his personal experiences of the Second World War. Although he couldn’t accept the prize in person, Lady Clementine Churchill accepted it on his behalf.

An Enduring Legacy

Churchill’s legacy has endured in the decades following his passing, ensuring that his achievements and memory will never be forgotten.

When Churchill passed away in 1965, he became the first person outside of the Royal Family to have a state funeral. In the same year, The Royal Mint produced a crown commemorating his life and Lady Clementine Churchill travelled to our site to strike one of the coins.

The editions of the Churchill medal included in our new Churchill Collector Sets feature the portrait of the former prime minister that first appeared on the 1965 Churchill crown.

You may also be interested

A Sovereign Fit for a Prince

A Sovereign Struck at the Outbreak of War

The Story of The Sovereign in Canada