On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked the naval base at Pearl Harbor, inflicting heavy damage on the US fleet. Britain’s Asian colonies were next and attacks on Hong Kong, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia) and the strategically important island of Singapore followed almost immediately. Japan’s best hope lay in a short war, quickly weakening US naval strength and capturing vital oil supplies, but the industrial might of the United States proved impossible to overcome.

The End of Expansion

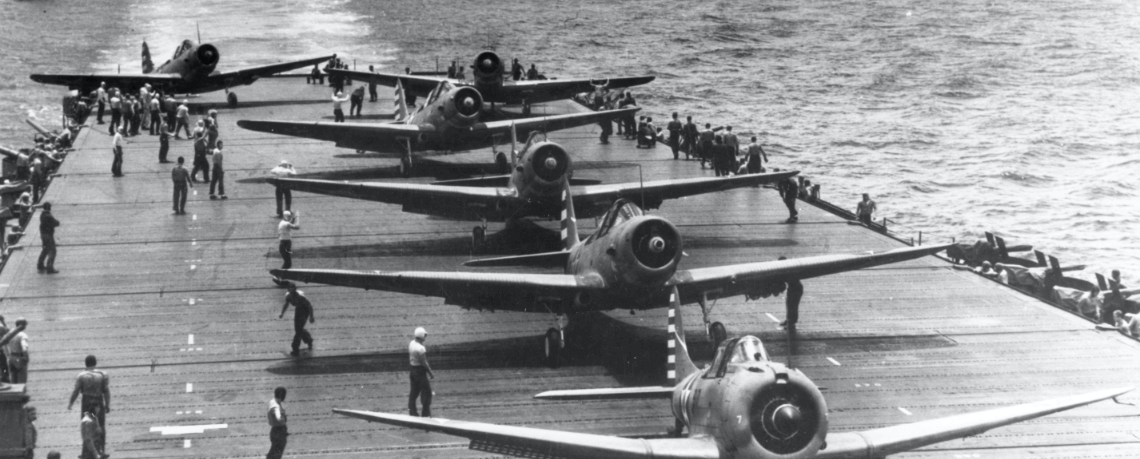

Japanese expansion was halted by the decisive aircraft carrier battle at Midway Island in June 1942, while the Allied fightback in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands removed the threat to Australia. Seizing the initiative, the US began a two-pronged offensive. In the south-west Pacific, General MacArthur advanced towards the Philippines. The main attack was in the central Pacific, where Admiral Nimitz fought an island-hopping campaign with his carrier battle-groups. The capture of islands such as Tarawa, Saipan and Iwo Jima saw heavy casualties on both sides.

The Forgotten Army

The British Fourteenth Army was a multinational force. Overlooked by the press, it was often referred to as the ‘Forgotten Army’. Forced into retreat from Burma in 1942, British and Commonwealth forces regrouped at the Indian border. Facing a tenacious opponent, difficult terrain and challenging weather conditions, the Allied campaign to retake South-East Asia was hard fought. The turning point came in March 1944 when Japanese troops tried to push British and Commonwealth forces back into India by destroying the bases at Imphal and Kohima. The advance was met with stout resistance, forcing the Japanese High Command to call a halt. From here, they were always on the defensive.

Fanatical Resistance

With Japanese forces stretched across Burma, China, New Guinea and the Pacific, Allied momentum proved too much. One defended island after another fell. On 1 April 1945, US forces landed on the island of Okinawa, only 350 miles from the Japanese mainland. Resistance on the ground was fanatical, while US warships, supported by the Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, suffered unremitting attacks by Kamikaze aircraft. By 21 June, when the island was finally taken, US forces had sustained 50,000 casualties. On the Japanese side, estimates suggest 110,000 casualties as well as 100,000 civilian deaths. While Okinawa was an overwhelming victory for the Americans, the ferocity of the resistance raised many questions about the likely human cost of any invasion of Japan.

The Manhattan Project

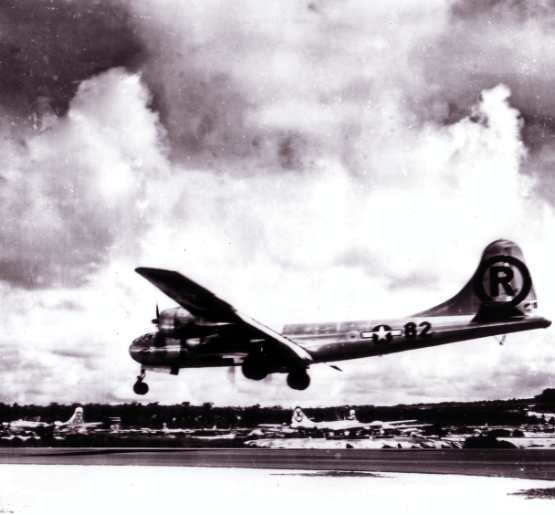

The capture of Okinawa gave the Allies a base to launch a seaborne invasion of Japan’s home islands. Code-named Operation Olympic, US General Douglas MacArthur was put in charge. Intensive bombing of its cities and a naval blockade had brought Japan to its knees. Defeat was a foregone conclusion but any invasion would incur terrible casualties. As Allied commanders planned for a November offensive, deep in the New Mexico desert a top secret research project was about to yield an alternative option. The Manhattan Project was the codename for the US led programme to develop atomic weapons. Led by Robert Oppenheimer, on 16 July 1945, at a remote location near Alamagordo, New Mexico, the Trinity Test saw the first successful detonation of an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer’s team developed two different types of weapon: a uranium-based design called the ‘Little Boy’ and a plutonium-based device known as the ‘Fat Man’. Both were used to devastating effect to bring about the end of the war.

The Potsdam Declaration

US President Truman, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met at the Potsdam Conference to discuss the war against Japan. On 26 July, the Potsdam Declaration was issued. The United States, China and the United Kingdom called upon the government of Japan to proclaim the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces. With no surrender agreement in sight, the decision was taken to use atomic weapons. Hiroshima was chosen as a target. On 6 August, the Enola Gay bomber plane dropped the ‘Little Boy’ bomb above the city causing unprecedented death and destruction. The hoped for surrender didn’t come. Three days later the city of Nagasaki was levelled. More than 100,000 people were killed by the two atomic bombs, while thousands more died from their injuries or the after-effects of radiation.

The Emperor Intervenes

The terrible destruction, combined with the Soviet Invasion of Manchuria, forced Japan’s hand. On 10 August, it offered to surrender unconditionally as long as the emperor remained sovereign ruler. The US insisted imperial authority would reside with the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers and on 14 August, following three days of heated debate, Japan finally surrendered. In the absence of any guarantee regarding the emperor’s sovereignty, the military sought rejection of the Allied terms, but Emperor Hirohito asked his ministers that they bow to his wishes and surrender unconditionally.

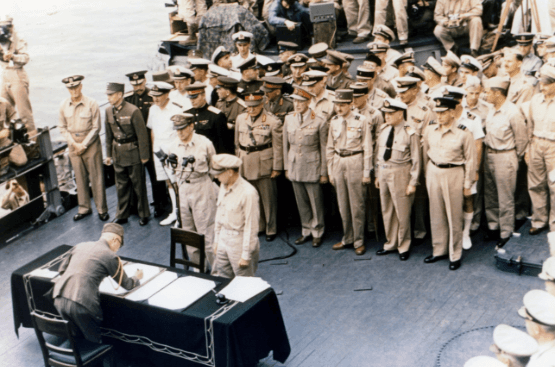

Japan's Formal Surrender

On 14 August, Britain’s new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, announced the news of Japan’s surrender at midnight, declaring a two-day national holiday, beginning with Victory over Japan (VJ) Day. Emperor Hirohito took to the airwaves for the first time to address the people of Japan, telling them that ‘the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage’. The broadcast was intended to stop attempts by the military to continue the war. On 21 August, Japanese fighting in China came to an end. Later, on 2 September, the formal instrument of surrender was signed by Allied and Japanese representatives on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. After six years of untold death and destruction, the Second World War was finally over.